Since ODR began to be discussed, developed and applied, which was as long ago as towards the end of the last century, it has commonly been thought of that there was an invisible “A” in the acronym so that ODR really referred to Online Alternative Dispute Resolution. That was understandable given that all instances of ODR, such as at eBay, were outside the mainstream resolution services at the courts or tribunals. That is changing.

2015 was the year when finally the “A” was thrown out, or at least, if it remains, can stand for “appropriate”. Consider these developments:

- A Report for the Civil Justice Council’s ODR Advisory Group recommended the setting up of HM Online Court which would change the “court” from a building into a readily accessible online service including all forms of ADR at its core and which, unlike, for example, the Small Claims Mediation service, would be so entrenched into the justice service as to be a mainstream part of the service for the overwhelming majority of those entering the “court”.

- A Report by Justice made similar recommendations for increased use of ODR within the justice system.

- A Report by the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Council of Europe recommended that all 47 Member States take steps to promote awareness of, and further develop, mechanisms for ODR.

- Public statements in support of the use of ODR within the justice system have been made by the Master of the Rolls, the President of the Supreme Court and the Secretary of State for Justice.

- The Interim Report of Briggs LJ into the structure of the courts fully supports the proposals of the CJC ODR Advisory Group.

The CJC’s ODR Advisory Group Report proposed a three tier justice system in which more resources, both financial and personnel, were focused on helping the public to better understand their rights, duties, liabilities and options (tier 1), as well as to triage, and access, the options for resolution with particular emphasis on facilitation through mediation and other forms of ADR (tier 2), rather than having a judge determine the case. When cases passed through tiers 1 and 2 without resolution, a judge would resolve online most cases that did not require evidence in person or argument on law (tier 3). Contrast the present situation where the emphasis of resource is applied the other way around.

Additionally, 2015 saw the Rechtwijzer 2.0 ODR service in the Netherlands go fully live. This is an “out of court” online justice service provided for the Dutch Legal Aid Board. It is a good example of the model envisaged in the CJC and Justice Reports. Powered by innovative technology provided by Modria.com Inc, a spin out of the ODR Departments at eBay and PayPal, and developed in partnership with “HiiL Innovating Justice”, the application offers legal diagnosis, self-triage, legal information and problem solving tools along with a platform on which to enable the parties to work together to resolve the issues, extending, where necessary, to include mediation. The first system is being used in family law disputes and is currently being developed for similar application in British Columbia. Later this year it is expected to cover landlord and tenant disputes with other categories of disputes scheduled for later launch.

Implications for lawyers

As a result of reference in the proposals for an online court to be one designed to be “lawyer free”, many see the Arrivals Hall of HM Online Court as also the Departure Lounge for lawyers. This is not the objective; quite the reverse. Whilst ODR is indeed disruptive to current practices, it opens up opportunities for lawyers to focus more on delivering cost-effective services at the high end of the skills scale than they are able to do without ODR technologies. Importantly, by significantly increasing access to justice and thus the number of disputes that the public are able to pursue through the justice system, it will increase the numbers of people going through its electronic doorway. Litigation lawyers will thus have a much larger market to which to offer their services.

By operating online, the cost of the lawyer’s time is lower and fees can be reduced, thereby widening the range of economically viable forms of representation in the sub-£25,000 category. Further, lawyers who unbundle their services will be able to offer such services at a rate that claimants may find economic: for example, offering advice on setting up and framing a case, or advice on a difficult point of law that has arisen (direct access barristers especially), or just online mediation advice and representation without going “on the record”, or going on the record late on to offer just advocacy at an online trial.

Lawyers who embrace ODR and seek to exploit creatively what is available will benefit over those who simply wish to be protected by old practices that have seen access diminish.

It is noteworthy that the Law Society is targeting their response to Briggs LJ’s recommendations for an online court not to the idea of the online court itself, but to the satellite issue of the cases to which it should be applied, suggesting, in the initial phase, that such should be limited to disputes up to only £10,000 in value rather than £25,000.

Effects of EU legislation

The public will this year begin to become more familiar in any event with the acronym of ODR itself, thanks to the effect of the EU Directive on Alternative Dispute Resolution for Consumer Disputes (2013/11/EU) as well as the connected EU Regulation on Online Dispute Resolution (524/2013). Together this European legislation effectively requires most businesses to act as the unpaid promoters of ODR.

Under the provisions of the Directive (implemented in the UK by The Alternative Dispute Resolution For Consumer Disputes (Competent Authorities and Information) Regulations 2015, as amended), all customers who have bought (offline or online) products or services for a purpose other than business, trade, profession or craft, and with whom the business had not resolved a dispute directly with them (and, with no value ceiling this can include high value transactions such as the sale of an ocean going yacht as well as building extensions, swimming pools etc) must now be informed by the relevant businesses of the web address of a provider of ADR that has been approved by a responsible authority in each country (in the UK, outside of regulated industries such as finance and banking, it is the Chartered Trading Standards Institute) as satisfying certain standards required by the Directive. Since such standards include using a system that enables claims to be raised, and information to be exchanged, online, the ADR provider must effectively also be an ODR provider.

Additionally, all European traders who sell online must now ensure that their website contains a hyperlink to an EC designed and run ODR platform. The primary function of the platform is to take in the complaint and refer the consumer to an approved ADR provider. Very few businesses are aware of this new duty on them as the Government has yet to properly publicise the requirement. So, for example, even Richard Branson appears unaware as those who seek to book a flight into space on Virgin Galactic are not being given a link from the website to the EC’s ODR platform. But even if Galacticos come back to earth with a bump and the astronauts raised a claim, under the Regulations Virgin are only required to point them to an approved provider of ADR but not to actually participate in the resolution.

No doubt in time the Regulations will start to be complied with at least from the point of view of referring dissatisfied customers to ODR services and, given that the acronym has been adopted to describe the online requirements, one can look forward to greater public awareness. Additionally, once HM Online Court opens up its virtual doors, it seems clear that, at least in consumer disputes, the approved consumer ADR providers will have increasingly more cases to deal with given that the self-triage and referral elements of tier 2 in the court will identify them as the most appropriate (retaining the “A”) and available option.

Whither ODR?

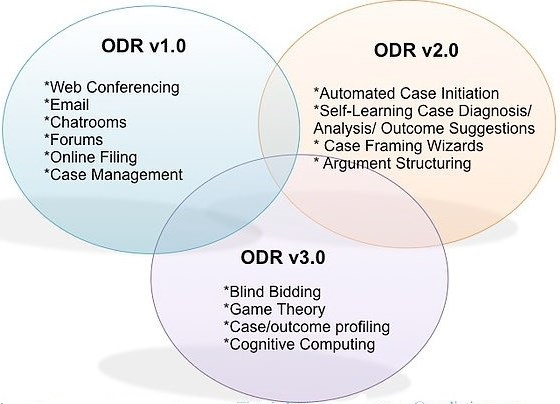

My main concern is that, by defining ODR in such simple terms as just filing and exchanging information online, in other words using the technology solely as a means of communication, the European legislation will hold back more innovative applications coming to the market. ODR systems can enable the public to better understand their position and prospects (there are systems operating now by Modria.com for handling taxation appeals in the US with buttons such as “Do I Have a Strong Case?”) as well as help with framing their cases and argument and even to the point of brainstorming mutual solutions. I have identified three versions of ODR in the graphic above, such as self-operated dispute analysis and triage as well as case framing and argument structuring assistance. On the very near horizon is predictive analytics, prioritisation assistance through game theory and, thanks to IBM Watson, as currently being exploited in the legal field by Lex Machina and by Ross Intelligence (brilliant name but no connection!) cognitive computing.

The latter may sound like the advance of the robo-lawyer or robo-mediator. In time, they will be with us, but why be afraid? Much of what we as lawyers do can be done by machines. Document assembly has been implemented for some time by lawyers, with clients now being offered hands-on access to the controls so they only need to pay lawyers to advise, check and tweak the output. But why not also in contentious work, taking clients through standard logic trees of questions to extract what their case is about, and better frame the case? Imagine having a MiniMe (as in the Travelodge TV ads) who would, in seconds, give you quality, focused, research on case law. Suddenly you can offer the benefit of empirical knowledge of the court, judge, and litigants in general, to your knowledge of text book law. You will still be needed for your professional judgment by those who can afford you. Importantly, the numbers of those who will be able to afford you will be massively increased, not just by the reduction in your time and fee, but by the much greater numbers of people able to access the Online Court in the first place.

Conclusion

All of this can in the near future, given enough commitment, be available to let the machine take the strain and free lawyers to do just what they are best at: applying high levels of skill and professionalism to the knowledge provided.

The Lord Chief Justice said recently that civil justice is now “unaffordable to most”. We, as a profession, should be ashamed of that fact and actively working for change. As with most other areas of service, technology is key to such change. ODR finally moves justice away from being accessible to all “like the Ritz Hotel”, as Justice Mathews said over 100 years ago, to being accessible to all “like a Travelodge”.

Graham Ross is a lawyer/mediator specialising in resolving shareholder disputes and is a leading expert in ODR. He is MD of The Mediation Room and Head of the European Advisory Board of Modria. He is a member of the Civil Justice Council’s ODR Advisory Group. Email g.ross@themediationroom.com. Twitter @mediationroom.

ODR Training. For those wishing to become trained in the field of ODR, Graham has just re-launched a new extended version of his ODR training course at www.odrtraining.com.