The Internet of Things (IoT) is, literally, the network of all the physical things connected to the internet. (Generally we now refer to things capable of connecting to the internet as “smart” things.)

We started with just computer terminals connected to the internet and that remained the way it was for 15 years or so. To that network of billions of connected computers we have now added billions of smart phones and tablet computers which have added many new ways in which we can interact with others on the network, whether it’s ordering a product just by scanning in its QR code, requesting a cab based on our location tracked via GPS, or finding out more about where we are or what we are looking at just by pointing at it. We’re also now purchasing smart TVs in large numbers, combining our thirst for broadcast TV with our thirst for on demand TV and social media services in particular. Our cars are increasingly smarter and we are also venturing into smart home automation: remotely controlling our central heating, security systems and other devices which can also automatically communicate with our suppliers.

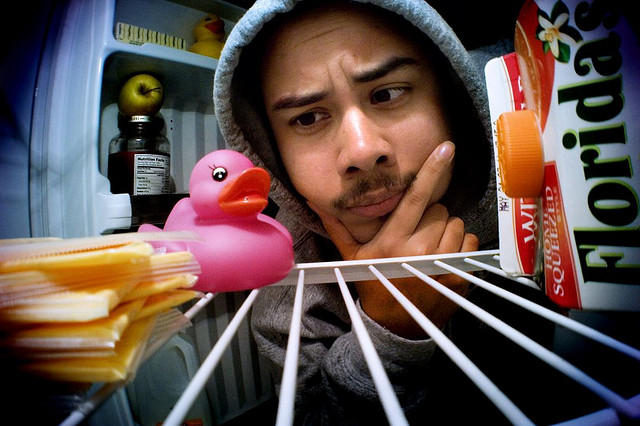

So far so mundane you may say in 2015, but – and this is what really gets the media excited – what about smart fridges?! What delights and perils are in store when everything can be connected to the internet?

The scale of the IoT and its consequences are vividly elucidated by Marc Goodman in an extract from his book Future Crimes in the Guardian:

The byproduct of the IoT will be a living, breathing, global information grid, and technology will come alive in ways we’ve never seen before, except in science fiction movies. As we venture down the path toward ubiquitous computing, the results and implications of the phenomenon are likely to be mind-blowing. Just as the introduction of electricity was astonishing in its day, it eventually faded into the background, becoming an imperceptible, omnipresent medium in constant interaction with the physical world. Before we let this happen, and for all the promise of the IoT, we must ask critically important questions about this brave new world. For just as electricity can shock and kill, so too can billions of connected things networked online. ”¦

For all the untold benefits of the IoT, its potential downsides are colossal. Adding 50 billion new objects to the global information grid by 2020 means that each of these devices, for good or ill, will be able to potentially interact with the other 50 billion connected objects on earth. The result will be 2.5 sextillion potential networked object-to-object interactions – a network so vast and complex it can scarcely be understood or modelled. The IoT will be a global network of unintended consequences and black swan events, ones that will do things nobody ever planned. In this world, it is impossible to know the consequences of connecting your home’s networked blender to the same information grid as an ambulance in Tokyo, a bridge in Sydney, or a Detroit auto manufacturer’s production line.

What are the legal issues?

The legal issues are of course broadly those we are currently grappling with on the internet, but arising in many new, often unexpected, contexts as human input and control is increasingly absent from transactions which take place between essentially dumb things programmed to act smart – “machine to machine” (M2M). Just as mobile computing has increased the opportunities for invasions of privacy, harassment, copyright infringement and more, so, as the IoT expands, we’ll have more and more types of interaction giving rise to legal issues.

Here are just some of them:

Security and privacy. Can the device be hacked or hijacked or data transmission be overheard so that data are stolen or otherwise misused?

Data protection. Individuals must be told about the collection of their data, and in the case of sensitive data individual consent will usually be required. There must also be lawful bases for the use of the data from their smart devices and tracking of individuals must be for legitimate purposes.

Liability. What happens when the machines get it wrong? Who will be liable?

Ownership. Who owns what when devices interact with each other and collect vast amounts of data?

Contracts. What will happen when machines buy and sell from each other? Will consumer laws apply?

Net neutrality. It is very possible that in the near future bandwidth demand will exceed supply and net neutrality will become vital to eliminating barriers and keeping costs down for consumers.

Patents. The extent to which many parts of the technology required for the IoT are patentable could become an issue.

Hat tip to Bird & Bird and Gordon Dadds for these points, extracted from their articles referenced below.

Further reading

SCL: The Internet of Things: the old problem squared

Bird & Bird: Data Protection, Privacy and Cybersecurity in the Internet of Things

Gordon Dadds: The Internet of Things: Highlighting the legal issues

Nick Holmes is Editor of the Newsletter.

Email nickholmes@infolaw.co.uk. Twitter @nickholmes.

Image: Fridge Surprise by Nestor Lacle on Flickr.

One thought on “The Internet of Things: an introduction”

Comments are closed.