Family law today is a cottage industry. Despite new entrants looking to offer national, commoditised legal services, most family law services continue to be offered and delivered in the traditional way by a large number of solicitor suppliers.

In 2013 there were about 13,500 solicitors practising family law in England and Wales – about 11 per cent of the total. Many of them are sole practitioners or work in small firms.

Most provide excellent, bespoke legal services to their local communities and long may they continue to do so. However, there is a risk for the public of lack of consistency which comes from this type of delivery model – a lack of consistency in relation to quality but also costs. This can cause confusion and can be disempowering for individuals who are seeking legal advice and support at a difficult time in their lives.

Family work can be very broad – and inevitably no-one can specialise in all the topics, private and public work, children and finances and so on. Also, not all lawyers work in the family field full-time – some combine it with other disciplines.

In addition to this, although since April 2014 we have a single family court, we have yet to achieve consistency of decision-making. An outcome in one locality can often differ from another.

And unlike other legal areas – such as conveyancing and PI – family law has not benefited until recently from significant investment or innovation.

Why change now?

What we have at present is a system that works for some but not for all, based on methods of delivery that have not changed for the last fifty years. However, the real driver for change arrived in April 2013 with the introduction of the LASPO reforms.

The “reforms” meant that unless there was proven domestic violence, no-one could access family legal aid services for finances or children related issues. It was hoped that mediation could provide an alternative and that mediation take up would dramatically increase – but without legal aid to see a lawyer in the first instance, referrals to mediation have, in fact, declined by at least 40 per cent.

Another direct result of the removal of legal aid has been unwilling litigants in person attempting to navigate their way through the complexities of the (often bewildering) court process. No wonder that senior judges have voiced their concerns about access to family justice and the current length of and delays in court process.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that some people who desperately need advice simply have not been able to access it. As a result they have been cast adrift, trying their best to resolve issues between themselves but with no guiding hand and the risk that already broken relationships are tested to destruction. And let’s not forget the people who didn’t access justice anyway – those who were too wealthy to qualify for legal aid but too poor to afford lawyers i.e. the vast majority of people in this country.

It’s only relatively recently that we have seen steps towards making family advice more accessible – by moving from hourly charges to fixed pricing and unbundling – so that clients can take greater control of their affairs and reduce costs by doing part themselves and getting advice or representation when they need it.

What we have, therefore, are those who used to get help are no longer receiving it; those who couldn’t access help before who want it to be affordable and the obvious concern for everyone to keep costs and conflict to a minimum.

In addition to this, the UK shares many similarities with other jurisdictions which are moving to ODR -a prosperous, wired and increasingly wireless society. Britain’s consumers (like other northern Europeans) are internet enabled and well used using the internet to access a broad range of products and services. We appear to largely trust the internet, despite the threat of cyber-crime.

And that trust largely comes from the dominance of large well-known reliable online brands – such as Amazon, eBay, Ocado, John Lewis, Tesco and so on. And implicit in those offerings is the consumer guarantee – of high quality and a means of settling disputes, coupled in eBay’s case with a supplier rating.

Conditions for success

First, it has to be available to everyone. We sometimes forget that people going through family crises don’t live normal lives. There isn’t always a PC on a desk at home. Therefore, it has to be available across all devices – whether that’s a traditional PC or laptop, a tablet or a smartphone. And it has to be reliable.

It has to be affordable for those using it, and the cost differential between it and other methods must be sufficient to make it attractive. In the early days of the project at least, it would seem sensible for there to be government financial support.

It must be comprehensive, offering the means to resolve a wide range of private law family disputes and issues.

And it needs to be supportive. The information has to be easy to digest – for example with video help guides and a high degree of logic so that people get all the information they need but not too much information.

It has to have an external mechanism to settle disputes which the parties themselves can’t. That could be as simple as a message to an online mediator setting out a statement which is agreed by the parties, a video conference or, if necessary, a face to face session.

Lastly, it needs cross-party government support and a commitment to make this a long-term trial.

Potential benefits

One of the main benefits is avoiding delay. People can get on with their lives without the emotional drain of conflict hanging around in their lives.

This should certainly result in less cost to the individuals, but also less cost to society. I recognise that attributing a figure to those benefits is difficult but it’s unarguable that there will be one.

Not all parties will be able to resolve their disputes this way. But it should work – at least in part – for the majority. For those, it’s much more likely that they will enjoy better future working relationships where there are children involved, and that means less need to go back to court.

Where people engage in reaching a decision it’s more likely that they can agree to vary it going forward, with or without online help, so there is less chance of later disputes and issues.

European Directive and eBay

The European Directive demands that all EU countries have formal ADR processes in place for all consumer matters by May 2015. The UK government is taking this seriously and acknowledges that we must do more to comply with the directive. This presents significant opportunities for the growth of ODR.

Obviously things go wrong – apparently 60 million times a year across the globe. EBay has devised a fiendishly simple dispute resolution process – and indeed it has to be in order to keep public confidence high. It simply has to work. It’s all backed up by seller reports where customers can review sellers.

So that’s the future perhaps for small traded items. In a world where the majority play fair an organisation with this scale and revenue can afford to create a process and support it. No lawyers, no courts and no fuss. What’s the read through for family breakdown issues?

Going Dutch – Rechtwijzer

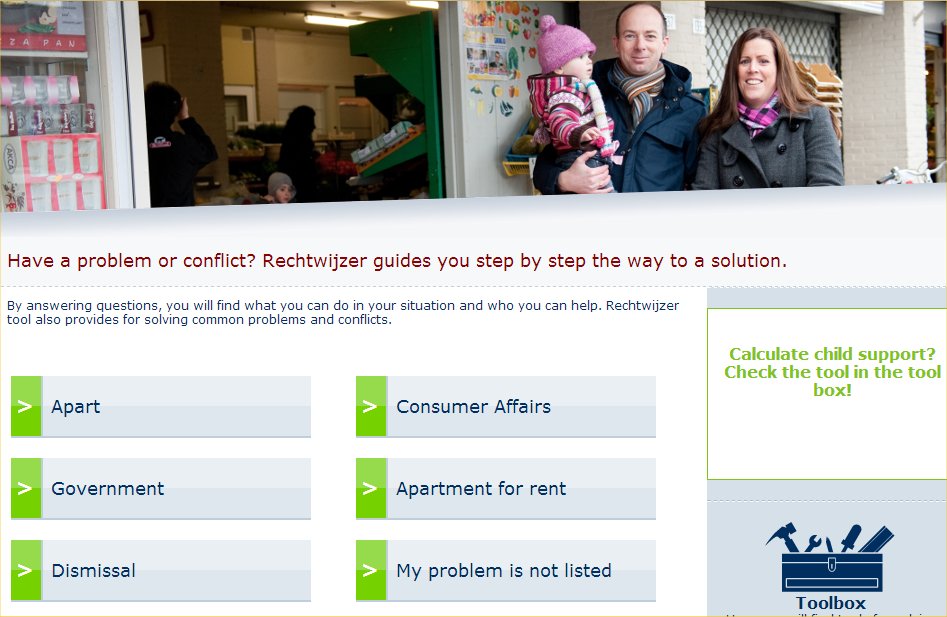

The Rechtwijzer, a “road map to justice”, was co-developed by the Dutch Legal Aid Board and University of Tilburg and is a bold attempt to cover many aspects of family law and relationship breakdown.

It was designed as a journey – a dynamic and iterative process which covers not only the legal aspects of divorce but also negotiation styles, strengths and weaknesses of the participants to help and support them to successfully negotiate. From July 2014 it has also been made available to clients who don’t quality for legal aid on a pay as you go basis.

Online you go through a series of questions about you and your circumstances. It supports individuals to understand their negotiation styles and encourages discussion and positive outcomes. It is all very clear and easy to follow – well, at least in English anyway (kind Google will translate it for you).

If the couple can’t resolve their issues by themselves then they can access online mediators or adjudicators for all or part of their issues.

Finally, agreements go before an independent lawyer to ensure that they fall within the spectrum of “fairness”.

Other examples of online mediation and dispute resolution can be found in British Columbia and Australia. Formal trials in the Netherlands and British Columbia have attested to the success and user satisfaction of both the process and outcomes.

Is this right for England and Wales?

It seems like a good idea but there are some issues.

The Dutch legal aid board was spending 15 per cent of its budget on family matters so a way of reducing that expenditure was critical for them. However, lawyers were understandably hostile to something that was not proven – where the results were uncertain – and which would obviously have an impact on their income but also on their numbers. That’s fine if everyone’s case is simple but what happens when the lawyers are gone when the case is highly complex?

The best systems are those which enable access to a variety of external services – it’s very rare that family clients present with just one issue and more often than not their affairs are more complex than initially appears. Sometimes, as lawyers, we have to take time to get clients to reveal everything to us when we have built up trust – and I just wonder whether clients will do that online so readily. And unless those matters come out then they can’t access the additional help they might need to get a fair and lasting outcome.

The problem with laws is that they change. Keeping a system up to date is expensive. The Dutch Legal Aid Board may simply decide it doesn’t have the resource to keep the system fully updated and be inclined to put the cost of updates on the private paying public. And that could have the effect of reducing demand and access to justice. Tangentially, one of the things I hope is that an ODR process for family disputes would be accompanied by a move towards a more systemised and simple form of family justice.

And there is a risk that it will create a two tier system: the poor get online help and the rich get the best lawyers. This is a conundrum. Clients who are poor don’t have a choice: they simply won’t have the means to go elsewhere. Yet their circumstances can often be more complex and difficult to resolve than those who have greater means. There is therefore the risk of creating a two tier system and regardless of how much help that is built into a system there remains a risk that the public perception will be that this is a solution which at best is for the poor or relatively poor.

Conclusion

In a world of increasing computer literacy and accessibility and reducing government and third sector funding, it must be right to see if we can increase access to justice by empowering separating couples to sort out their issues and move on.

There is good news on this front as Relate have recently secured funding from Google to develop an ODR for families.

Christina Blacklaws is Director of Client Services at Cripps, a large corporate/real estate and private client practice. She is Women Lawyer’s Division representative on the Law Society Council and an executive member of the Family Justice Council. Previously she managed a succession of innovative legal businesses before joining the Co-operative to launch their family law service in 2011.

Email Christina.Blacklaws@cripps.co.uk. Twitter @Blacklawslaw.

One thought on “ODR in family law”

Comments are closed.