The Government recently published a White Paper, “A pro-innovation approach to AI regulation,” setting out its proposals for AI regulation, in conjunction with an impact assessment and consultation paper. Jo Frears, IP & Technology Leader at Lionshead Law, considers some of the key points.

The meaning of “AI”

The White Paper acknowledges that there is no single accepted definition of artificial Intelligence (“AI”) and so it defines AI as being technology that has characteristics of either “adaptivity” or “autonomy” or both.

Adaptivity refers to the initial or continual training of the technology and through such training, operating and performing in ways that are both anticipated and expected, and/or in ways that were not planned or intended by the programmers.

Autonomy refers to the ability of the technology to make determinations or decisions without human input.

By choosing not to define AI rigidly by reference to specific technologies or applications, but by the characteristics of its functional abilities, it hopes to “future -proof’ the regulatory framework. IP lawyers might equate this to a “look and feel” test and the idea for being non-specific has some merit. Where the lack of specific definition lets itself down is that it claims there is no need for “rigid legal definitions … as these can quickly become outdated and restrictive,” but without them, the range of AI is potentially so vast already and the unanticipated new technologies so broad, that this may become a framework that is at once too broad for the small applications such as chatbots and not broad enough for the types of generative AI already thinking of new ways to deploy themselves.

As lawyers we need to be aware that there is a risk for law when the lack of clarity around expectation and intention of outcome and the autonomy of a non-corporeal entity to make decisions not based on human input or judgement makes it difficult to assign responsibility for outcomes made by that technology. In lay terms, how do you provide human-centric regulation for a non-human decision maker operating adaptively (ie in ways AI devises) and autonomously (ie in ways AI determines based on the data it has learnt)? If however you can determine what the field markings of the regulation should be, you can at least get on to a level playing field. If that regulatory field can be marked out and the game players identified, it is possible then from a legal perspective to determine who is responsible for that and who therefore owns the AI’s decisions, output and risk.

Where the White Paper succeeds, is in identifying that there is a risk for public trust where there is a lack of regulation and that there is a need to build confidence in innovation. It is this driver and the desire to make the UK a leader in AI that has ultimately led to the consultation that has been ongoing since 2017 and has culminated in this White Paper. What is ironic is that this White Paper, with its stated desire for “an AI-enabled country” has been published just at the tide of opinion seems to be turning against AI and as thought leaders and technologists call for the brakes to be applied to AI development.

Legal challenges posed by AI

Since the Statute of Anne (1709), the law has sought to protect the creators of original works and to control the right to copy creative endeavours; first to control the means to print, then to ensure that patrons did not find their investment undermined with multiple copies and later to encourage and reward for inventiveness.

Different types of AI create different legal issues.

Generative AI is the one that seems to be firing imaginations and raising legal flags currently. Generative AI uses large language models that sequence and predict next words in word sequences to answer questions, produce emails and voice messages, text, blogs, poetry, essays, books and program code as well as to create images based on learning words used to describe images and then apply those to creating artwork for sale, social media content, marketing and product design (everyone from Deloitte to Danone, Muller to Mattel are using it). The output can be generalised or specialised and often generative AI provides unusual or unexpected results: the sort of thing we expect from creatives and outliers in our communities to surprise us with, imputing to it more human-like qualities. Generative AI can predict the outcome of trials based on precedent and facts and output sequences in all of the natural sciences, including personalised medicine. All of which has traditionally been protected by intellectual property and common law rights such as copyright works, confidential information, trade secrets and patents.

The rights of developers and of AI itself to hold intellectual property rights in output from generative AI is under discussion and presents challenges both in terms of how AI content is marked and rights in it are asserted, and even if AI is composed (or possibly even contrived) or is created? Does the output of Generative AI meet the “labour” test required for creation of original work or does the fact that the “purpose” of Generative AI is to create such works mean it can never achieve the digital equivalent of “sweat of the brow” because its only purpose is to originate creative output and nothing more, and that is done electronically?

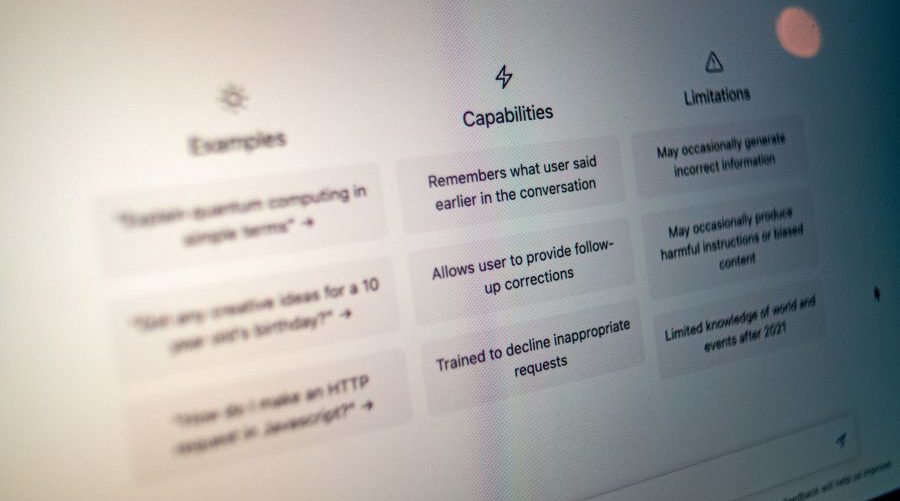

Conversational AI (chatbots) can answer queries and appear to interact with humans whilst maintaining the frame of the enquiry, essentially carrying on conversations in a natural language form. We have become used to chatbots being part of our online lives and their use will inevitably expand into numerous use cases as the input improves and development costs drop.

Whilst some chatbots have been criticised for reproducing clichés and prejudices – largely due to the inherent bias of the data they are trained on – the ability to sue the AI program itself does not exist and the opportunity to call out the bias by suing the developers is limited and largely lies in the regulatory sphere rather than the court.

What is crucial is that, as the use of conversational AI as a tool for human-like interaction provides opportunities for economic growth and engagement, the benefits have to be balanced with protecting consumers and users from false or misleading information – as noted recently by Sarah Cardell, Chief Executive of the Competition and Markets Authority. Even as more entry level bots become available, it is likely these will be available on click-through licenses under commercial B2B terms or at least on “buyer beware” and “as is” bases, but, as these become more commonly deployed, obligations for accuracy and balanced output as well as fitness for purpose may be imposed by statute.

Knowledge Management AI allows text and video knowledge to be organised and shared, mostly for training purposes. The next iteration of this type of AI will be personalised use directed at end-users; initially it is likely to be specific knowledge of risk and likely outcomes for large businesses, financial institutions, insurers, law firms and high net worth individuals. Invariably knowledge is power and disinformation disempowers users. The application of AI to knowledge management and arguably controlling access to knowledge is ethically particularly challenging.

The machine learning involved in creating generative AI requires truly massive data sets to be used (GPT-3, the predecessor to the current much-hyped GPT-4 was apparently initially trained on 45 terabytes of data and employs 175 billion parameters or coefficients to make its predictions, with a single training run alone costing $12 million) which has naturally resulted in the major tech players being those who are able to create Generative AI tools.

Traditionally, those technology mega-corps have been able to side-step, dilute and generally inveigle ways to prevent too much regulation of their tools and tech, whilst all the while benefitting from good old patent prosecution, copyright, licences and court cases. At the South by Southwest Interactive Conference in Austin, Texas in March 2023, various scenarios of regulation and AI application were explored and (by all accounts) hotly discussed. Arati Prabhakar (Director of the White House’s Office of Science and technology Policy) is quoted as saying, “This is an inflection point. All of history shows that these kinds of powerful new technologies can be used for good and for ill,” and Amy Webb of the Future Today Institute suggested AI could go in only one of two directions in the next ten years. Either focusing on “the common good with transparency in AI system design and an ability for individuals to opt-in to whether their publicly available information on the internet is included in the AI’s knowledge base” and with AI serving as a “tool that makes life easier and more seamless.” Or resulting in less data privacy, more centralisation of power in a handful of companies and AI that anticipates or determines user needs and thereby stifles choice. As the flipsides depend on large tech companies taking responsibility for their development, Ms Webb apparently does not rate the chances of the first scenario being achieved at anything more than 20 per cent.

But the recent (March 2023) open letter signed by luminaries such as Yoshua Bengio, Elon Musk and Geoffrey Hinton (as well as 22,500 others) calls for a halt to all AI development due to the unexpected acceleration of the AI systems under development and the race to develop AI that passes the Turing test and the fact there is “no guarantee that someone in the foreseeable future won’t develop dangerous autonomous AI systems with behaviours that deviate from human goals and values.” For “guarantee” read “legislation, regulation, oversight or control to prevent” and for “won’t develop” read “will stop, prevent or punish” and this is a stark reminder that law in this area is all but non-existent.

It is interesting to note though many regulatory entities have recently sprouted and spouted on the subject of regulation. In Europe, the European Centre for Algorithmic Transparency (“ECAT”) was launched in April 2023 to focus on oversight of large online platforms and very large online search engines under the Digital Services Act and deliver evidence of breaches of the DSA and its sister-act the Digital Markets Act to regulators and prosecutors. Now, with this White Paper, the UK Government is also promoting not law, but regulation; not sanctions, but frameworks; not action, just discussion. The real question is whether that is now or will ever be adequate?

Current regulation of AI

Currently the regulation of AI in the UK is a salmagundi of existing law. An Accountability for Algorithms Act remains at the bill stage and none of the current legislation directly addresses AI creation, use and application and it all is technology neutral. That is to expected as the laws that could be applied to AI cover laws enacted over 600 years from tort (for negligence and civil wrongs), to the Electrical Equipment (Safety Regulations) of 2016, with discriminatory outcomes of AI being addressed by the Equality Act 2010, consumer rights in the Consumer Rights Act 2015 and the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008, the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, the Data Protection Act 2018; the list is extensive of laws that can be applied to AI even if they never anticipated it.

The White Paper acknowledges that there are “gaps between, existing regulatory remits” and that “regulatory gaps may leave risks unmitigated, harming public trust and slowing AI adoption,” and it cautions that regulators (and presumably regulations also) must be “aligned in their regulation of AI” to avoid an excessively complex and costly compliance regime, and particularly to avoid duplicate requirements across multiple regulators.

Proposed new regulatory framework

The White Paper proposes “balancing real risks against the opportunities and benefits that AI can generate.” Although the guiding hand approach does seem to have been welcomed by commercial industry, it is almost certainly likely to be dismissed as political cant by the technology industry. The key threads of the regulatory framework, once this is built, will be “creating public trust in AI” and “responsible innovation” by joining the global conversation on it.

The regulation looks to be “agile” with a flexible regulatory approach to strike the balance between providing clarity, building trust and enabling experimentation. To do this, the regulation will be:

- Pro-innovation

- Proportionate

- Trustworthy

- Adaptable

- Clear

- Collaborative

The Regulations will include cross-sectoral principles, with application of the principles being at the discretion of the regulators. The risk remains that the regulators are toothless lap dogs in the face of AI, despite the best intentions of agile regulation and regulators. To avoid this, Government has published a Roadmap to an effective AI assurance ecosystem in the UK for developers, hoping to make ethical and transparent development the norm. To bolster the Roadmap, Government also proposes a Portfolio of AI assurance techniques to showcase best practice and technical standards of risk management, transparency, bias, safety and robustness as benchmarks. Again, noble intentions, but to draw a parallel with products, for every certified original item sold on Amazon there are hundreds of knock offs that avoid or ignore the regulatory regime entirely and AI could face the same challenges in terms of policing.

The importance of international standards

The White Paper does not propose new law and so no additional territorial applicability is required. As the UK recognises the need for a collaborative approach across sectors, disciplines and geographical borders for AI, the White Paper proposes further engagement in the global AI regulatory conversations. How this will be manifest is by continuing involvement in the UNESCO Ethics of AI Recommendations and participation in partnerships such as the Global partnership on AI, the OECD AI Governance Working Party, G7 and at the Council of Europe Committee on AI. The White Paper proposes this is done whilst UK Government continues to press for standards development via its involvement with the International Organisation for Standardisation and International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC), the British Standards Institution and the Open Community for Ethics in Autonomous and Intelligent Systems (OCEANIS).

Next steps

The White Paper concludes that over the next 6 months, Government will continue to engage with industry and the public and will publish the AI Regulation Roadmap, identifying key partner organisations and existing initiatives that will be scaled-up or leveraged to deliver the required regulatory functions. In the 6 to 12 months following that, the organisations chosen to deliver the regulatory functions will be announced and Government intends to publish a draft central, cross-economy AI risk register for wider consultation. It also proposes that a pilot regulatory sandbox or testbed will be created and feedback from the pilot received.

Whilst the next steps are prudent, they smack of feeling a need to do something without actually having real impact. AI is happening now and the pace of its use and growth is faster than the White Paper seems to provide for in all of its talk of agility and regulatory flexibility.

Implications for legal practice

The bots are coming and are already in use in law and in business. Our clients expect it and our businesses require it. As practitioners whose role it is to anticipate risk, it is unconscionable to suggest that AI will not impact the legal sector, particularly in terms of client engagement and knowledge management and if disruption to legal practice was perceived as being likely to come from Google or Amazon as few years ago, AI has begun its stealthy overhaul already.

The ability of good AI to make better judgements and assess risks more accurately should be embraced, but the acceptance of its ubiquity should not. Elements of bias, deep-fakes, misleading and inaccurate output and outright infringement need to be addressed. A kite-mark approach is not adequate and AI is too ‘big’ (and will soon be grown up and clever) to ‘self-regulate’.

The training of human lawyers in interactions with early societies and their strictures, with historic text, contract, precedent, law, campaigns, shifts in cultural norms and engagements with other humans is as unique as each lawyer. Bringing this to bear, lawyers have been and remain part of the conversation on AI; the ethics of programming and the outcomes of it. They need to remain such, not just as observers but as active arbiters of social truth and as vocal custodians of the value of human-based, empathic experience and the application of actual precedent to people’s disputes, societies’ values and decision making and, crucially, free-will.

Joanne Frears is IP & Technology Leader at Lionshead Law, a virtual law firm specialising in employment, commercial, technology and immigration law. She advises innovation clients on complex contracts for commercial and IP matters and is a regular speaker on future law. Email j.frears@lionsheadlaw.co.uk. Twitter @techlioness.

Photo by Emiliano Vittoriosi on Unsplash.