Open access to case law in England and Wales is in a very poor state of health, both in terms of the amount of case law that is freely accessible to the public and in terms of the sustainability and development of the open case law apparatus in this jurisdiction.

It is true that the launch of BAILII in the early 2000s radically improved the public’s ability to access judgments and continues to provide a service of immense value. However, the simple fact is that nowhere near enough judgments from England and Wales’ superior courts are available on BAILII.

Efforts to increase public access to the decisions of judgments in this jurisdiction are being hampered by a range of systemic obstacles, including a general lack of awareness among judges, government, practitioners and commentators that a problem even exists, and a lack of understanding of how the judgment supply-chain in England and Wales works and why it is defective.

Why provide open access to case law?

More clarity on the objectives of the provision of open access to case law is a good starting point. Being clear on what it is that we are trying to achieve allows us to more robustly assess our progress against the goals of open access and, perhaps more importantly, understand the obstacles that need to be overcome.

“Open access to case law”, to my mind, boils down to providing access that is free at the point of delivery to the text of every judgment given in every case by every court of record (ie every court with the power to give judgments that have the potential to be binding on lower and coordinate courts) in the jurisdiction, save where restrictions have been imposed preventing the dissemination of the judgment (for example, where national security concerns or the identification of vulnerable persons is a risk).

The goal is first and foremost about providing access to the words used by the court when giving judgment in every case.

If I’m right about the goals of open access to case law, the next question we need to be ready to answer is: why bother providing free access to the text of all judgments given in every court in the first place?

There are at least four justifications for the provision of open access to case law.

The rule of law

In common law systems such as England and Wales, judges, in a broad range of circumstances, are able to make new laws or modify the scope of existing laws. There are any number of ways of casting that statement into tighter, more legalist language, but the essential point is that the words used by judges can, and often do, change the list of rules that govern what we can and can’t do and the penalties we are liable to incur if we break those rules.

Because of this, in an ideal world, We, the People would have some way of finding out what those rules are so that we are able to regulate our conduct to ensure we do not violate them and to know what our rights are if we suffer as a result of someone else’s breach of the rules.

The closer we move towards the open access to case law goal, the closer we get to being able to identify the rules that we are required to abide by.

The equality of arms

Accurately ascertaining what the law says on a given issue is far from straightforward. Even the most apparently trivial legal problems potentially involve issues of substantive or procedural law that require the skill and expertise of a practising lawyer to marshal.

The party to a dispute with access to a lawyer should in theory have at least two advantages over the party that does not have access to a lawyer:

- the advisor will have expertise in the substantive law and procedure applicable to the dispute; and

- the advisor will have the advantage of multiple, industrial-strength tools to help them determine what the applicable law actually says.

The party to the dispute who lacks the means to access these two resources is therefore obviously at a correlating disadvantage. They’re outgunned and probably outnumbered. There is an inequality of arms. Cuts in legal aid and, in many cases, the absence of legal aid altogether, increase the number of disputes in which one side is bringing a knife to a gunfight.

The closer we move towards the “open access to case law” goal, the more that state of inequality is reduced. Even if true equality cannot be achieved, some degree of access to the material governing the determination of who is likely to win and who is likely to lose begins to level the playing field. That’s a good thing.

Dispute reduction

The ability to form a reasonably accurate view of what the rules say on a given issue increases our ability to intelligently pick our battles and to resolve disputes before they go anywhere near a court or some other costly method of dispute resolution.

It may be hard to swallow, but if a litigant-to-be at least has the means of establishing that they probably do not have a leg to stand on (or has the other side bang to rights), more disagreements can be dealt with before lawyers get involved.

The closer we move towards the “open access to case law” goal, the greater our ability to resolve disputes before they evolve into nasty, expensive and protracted echoes of Jarndyce v Jarndyce.

Transparency

Courts are public institutions, financed by public funds. Judgments are their unit of activity. Those units of activity should be open to public scrutiny and study. Judgments are public information (unless, there’s a good reason to keep their content secret).

It may well be that nobody ever bothers to look at them, but that’s not the point. The point is that if judgments are only meaningfully accessible on systems we have to pay to access, they are not meaningfully accessible to the public.

How open is case law in 2018?

We are able to assess the current level of “openness” of case law by comparing the number of judgments available on BAILII for any given year against the number available for the same year on the major UK online research platforms.

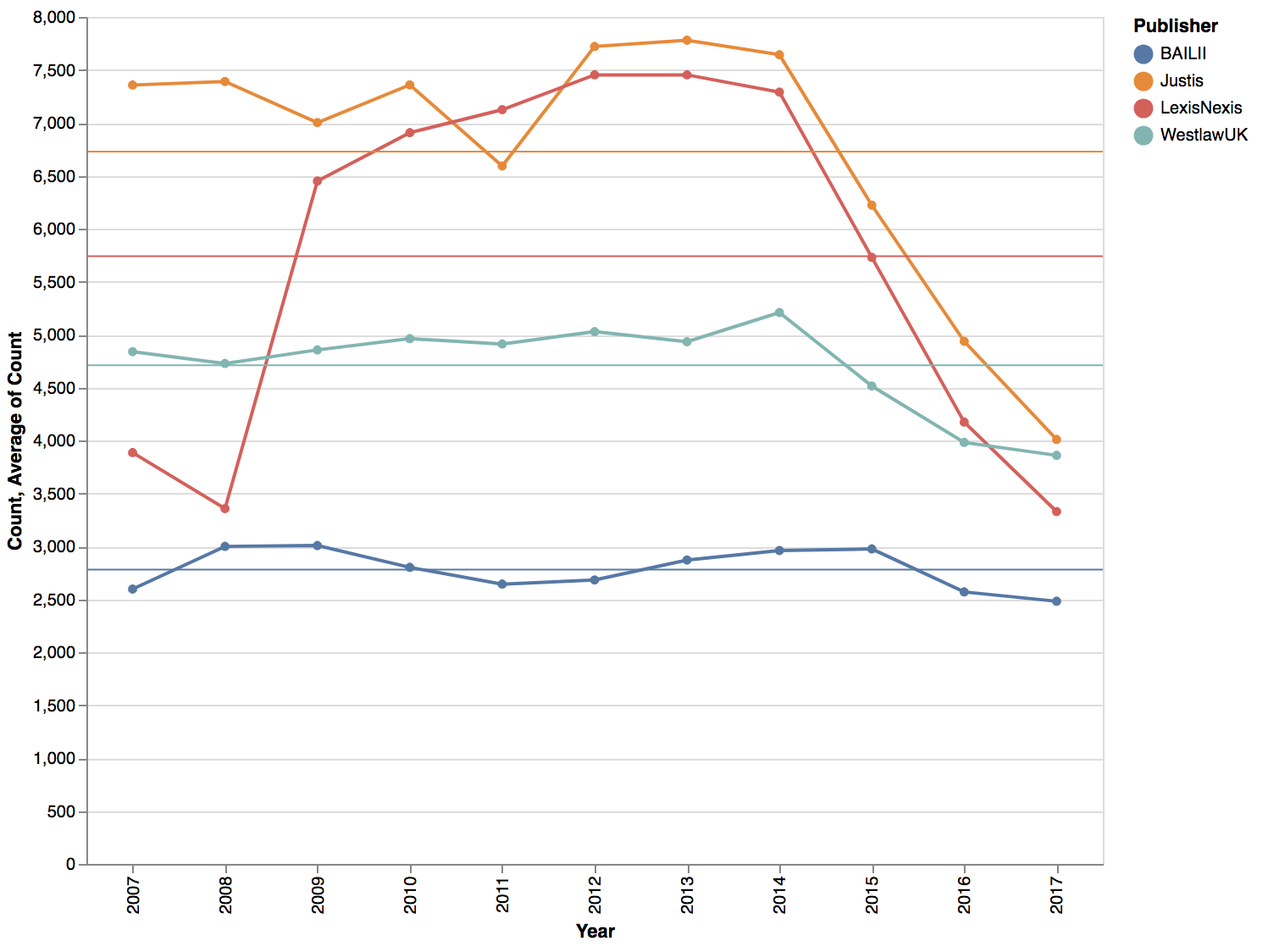

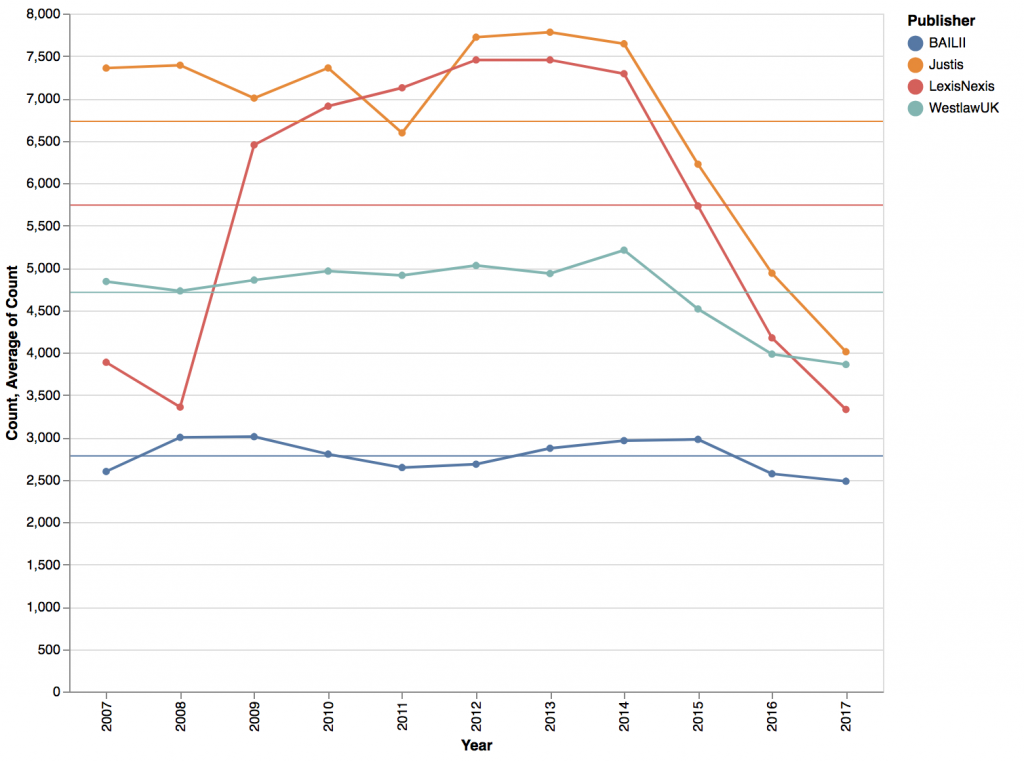

The analysis that follows is based on a side-by-side comparison of the quantity of judgments available on BAILII between 2007 and 2017 with the quantity of judgments available on three major UK subscription services, JustisOne, LexisLibrary and WestlawUK.

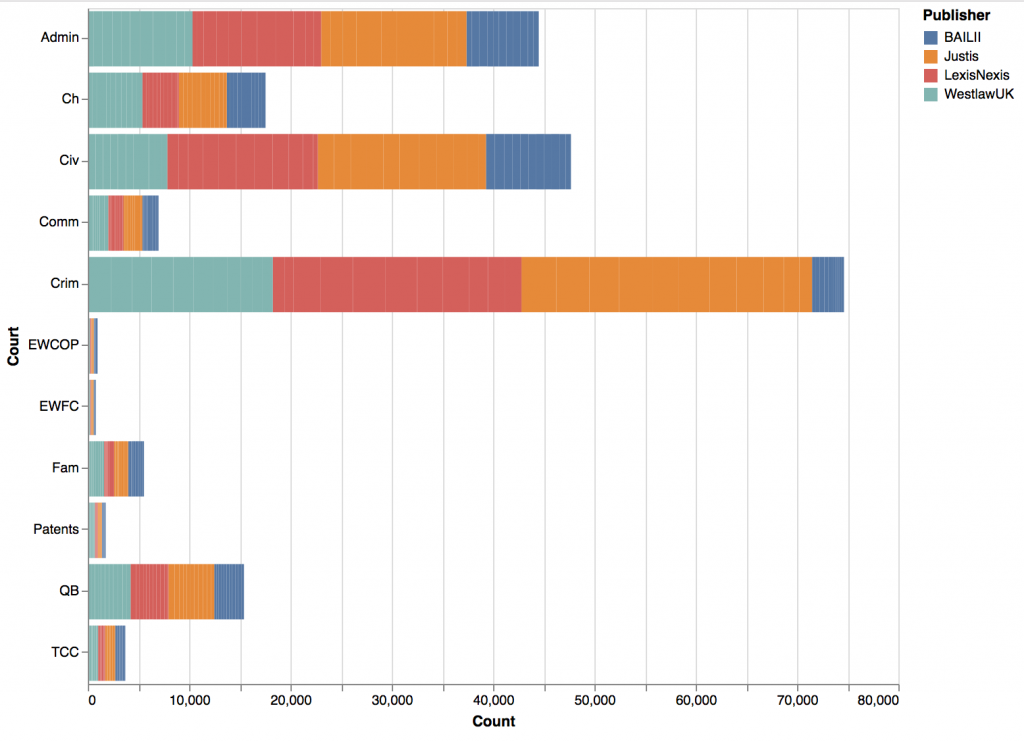

The following courts were included in the analysis: Administrative and Divisional Court, Chancery Division, Court of Appeal (Civil Division), Court of Appeal (Criminal Division), Commercial Court, Court of Protection, Family Court, Family Division, Patents Court, Queen’s Bench Division, Technology and Construction Court.

Data and analysis

According to a high-level analysis of the number of judgments available on each platform for the period 2007 to 2017, JustisOne ranks first with 74,010 judgments published, LexisLibrary has 63,148, Westlaw 51,813, and BAILII comes in last with 30,583.

Assuming JustisOne’s total for the period represents the totality of available judgments, the “open law deficit”, namely the number of judgments that are inaccessible on BAILII is 43,427.

Coverage by year

The chart plots the number of judgments published on each platform for each year. Apart from the fact that BAILII is shown to be well behind the commercial platforms year on year, two interesting patterns emerge. The first is the sudden drop in volume of coverage on JustisOne and LexisLibrary from 2017, which is attributable to a sharp decline in the number of judgments from both divisions of the Court of Appeal and the Administrative Court published on their platforms. The second is the stability of BAILII’s curve, which is commented on later.

Coverage by court

An analysis of the data for each publisher’s coverage by court provides a clearer of view on where BAILII is falling short. By and large, BAILII’s coverage roughly tracks the coverage provided by the commercial publishers, except in both divisions of the Court of Appeal and the Administrative Court where BAILII’s coverage lags far behind.

Accounting for BAILII’s lack of coverage

The data clearly demonstrates that there are serious gaps in BAILII’s ongoing coverage. Why do those gaps exist?

The judgment in any given case can be given in one of two ways. The first is known as a “hand down”, which is where the court reserves judgment at the conclusion of argument and returns to court at a later date with a written judgment in hard copy. Courts tend to reserve judgment in complex or serious cases. Electronic copies of handed-down judgments are routinely sent to BAILII for publication by the clerk to the judge giving judgment.

The second method by which a judgment may be given is known as an “extempore” judgment, which is where the court delivers its judgment orally very soon after the conclusion of argument, often within a matter of minutes. One would expect judgment to be given extempore in straightforward cases that do not involve complex issues of law or fact and, for this reason, they confer the practical advantage of enabling the court to give judgment immediately.

Notwithstanding the efficiencies conferred by extempore judgments, they present significant challenges when it comes to opening them up for public access.

An oral judgment is captured by the court’s recording equipment as it is delivered. For BAILII to be able to publish these judgments, it needs to be able to obtain the transcribed versions of them. The process governing the transcription of the recordings of extempore judgments into a form suitable for publication on an online platform is needlessly complex and beyond the scope of this article to examine comprehensively. However, it is sufficient for present purposes to focus on the transcription of extempore judgments from both divisions of the Court of Appeal and the Administrative Court.

Transcription of extempore judgments

The Ministry of Justice or HMCTS (it is currently unclear which), outsource the transcription of extempore judgments to the private sector. Under the current contracts, all extempore judgments given in the Administrative Court (including the Divisional Court) are transcribed by a company called Opus2. All Court of Appeal extempore judgments are transcribed by a company called Epiq.

So far as I am able to tell, Opus2 and Epiq’s business models are premised on two streams of revenue. The first stream of revenue comes from the state (ie the Ministry of Justice/HMCTS), which pays the transcription companies to transcribe the judgments. The second stream of revenue comes from legal publishers and litigants – the former group purchasing transcripts in bulk for republication in raw form or for use in a series of law reports, the second group purchasing transcripts on an ad hoc basis, presumably to consider grounds for appeal.

The main publishers of case law in England and Wales (Thomson Reuters, LexisNexis, Justis and the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting) pay large annual sums to these transcription agencies for an ongoing supply of judgments for reuse. BAILII cannot afford the sums involved and is therefore unable to obtain the same data.

The current arrangements governing the transcription of extempore judgments run completely counter to the tenets of open access. Moreover, public funds are being spent but no public benefit is ever realised (indeed, the Ministry of Justice ends up paying twice because it also needs to buy licences to the platforms).

I noted earlier that the curve of BAILII’s coverage is stable. The reason for this is that in the absence of the extempore judgments, BAILII’s coverage is confined to judgments handed down. The stability in the curve is reflective of the year-on-year steadiness of the number of handed-down judgments.

The way forward

This article has attempted to demonstrate that BAILII provides only partial access to the total number of judgments given in England and Wales’ superior courts each year. This will remain the case unless and until the Ministry of Justice and HMCTS recognise that a problem exists and that it is within their power to solve.

Two paths are available for the government. The first is what I would refer to as the open access “lite” model, under which government would continue to outsource extempore judgment transcription on the proviso that the transcription agency provide the Ministry of Justice with a copy of each transcript as soon as it becomes available, which could then be provided to BAILII for publication at no charge.

The second path, which I favour, I would refer to as the open access “ultra” model. Under this model, the government would bring all transcription in house and the transcripts would be made available online by the government in a form that is suitable for republication, reuse and data analysis (much like primary legislation on legislation.gov.uk).

Either way, nothing will change until the powers that be recognise that there is a problem, take the necessary steps to understand the mechanics of the problem in detail and set about tackling it.

Daniel Hoadley, barrister, is Head of Marketing at the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales. He blogs on design, literature, technology and some law at carrefax.com. Email Daniel.Hoadley@iclr.co.uk. Twitter @DanHLawReporter.

Two observations: first, the problem of extempore judgements seems to closely resemble similar problems with so-called “unpublished” opinions in the US and Canada, a matter about which a great deal has been written. Not all of that writing favors the availability of non-precedential opinions, but it’s hard to comment intelligently on BAILII’s situation if, like me, you don’t know how significant the extempore judgements actually are. Has any ever been considered a leading case?. Second, open access offers benefits far beyond those that are primarily in the province of lawyers or of people who are parties to current disputes. I once gave a talk on the subject, written up here: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/open-access-law-talk-un-thomas-bruce/ . Comprehensiveness is a worthy goal, for many more reasons than you set out here, but sometimes it is a costly and impractical one, and it’s hard to judge whether that’s a compelling factor here, absent any information about the precedential value of extempore judgements.

I know from experience that the JustisOne database is far from complete. When the late lamented Casetrack went out of business a couple of years ago, JustisOne claimed to have acquired their database of cases. I signed up to JustisOne (with a number of colleagues from chambers) on that basis, but subsequently it became apparent that there were a large number of cases missing and in fact JustisOne had nowhere near the comprehensive coverage of Casetrack. So I still don’t know what happened to Casetrack’s database but if Bailii can get hold of it, it would be a very valuable resource indeed.

Thanks Daniel for pondering this situation.

“BAILII’s coverage is confined to judgments handed down.”

Well kind of – but for 2018 BAILII has 70 Opus2 Admin judgments and 143 Eqip Court of Appeal judgments. A total of 372 judgments from Opus2 and Eqip from all UK and EW courts. Of course small beer compared to the commercial publishers.

I thought, perhaps wrongly, that Lexis helped with the transcription of primary legislation for legislation.gov.uk

Joe