“Every decision is binding no matter whether it is reported in the regular series of Law Reports, or is unreported. Once you have the transcript, you can cite it as of equal authority to a reported decision. It behoves every counsel or solicitor to find, if he can, a case – reported or unreported – which will help him advise or win his case.” – Lord Denning

In the days of printed law reports, there was a very real upper limit to how many cases could be reported – you can only fit so many in a book.

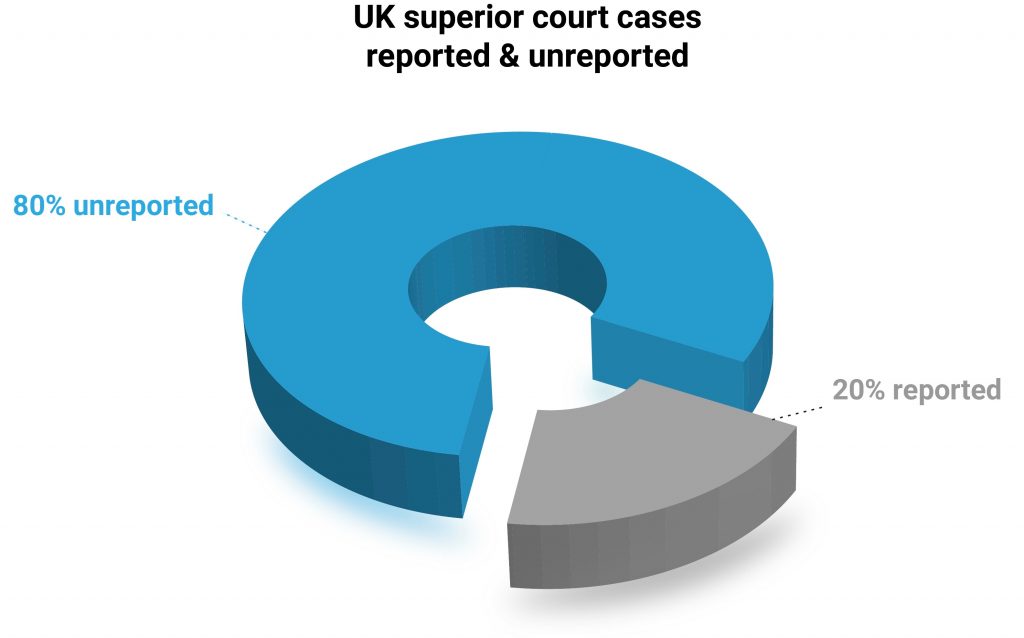

With digital content, no such physical problem exists, but other constraints remain. The process of producing high-quality reports of lengthy judgments is time-consuming and expensive. Consequently, fewer than 20 per cent of UK higher court cases end up in law reports – either leading or specialist series (based on the number of reported and unreported cases in the Justis database of UK superior court judgments).

It’s worth noting this limit is simply indicative of resources, rather than legal significance. It is a statement that only 20 per cent of cases can be reported, and says nothing about how many should be.

Of course, part of the job of the skilled law reporter is selection – it makes sense to devote time reporting only cases of interest i.e. those which set a precedent, say something substantive about the law, or have particular distinguishing facts. However, it is impossible for a legal practitioner or consumer to know the mind of the law reporter, or have any real insight into the selection process. More often, it is simply assumed that the collection presented in a reported volume or series is comprehensive, or at least “all you need to know”.

It would be far more realistic to acknowledge that any qualitative selection process will be to some degree subjective. The myriad factors involved in deciding whether to report will include the socio-political climate of the time, and necessarily have a temporal bias. A dissenting judgment, considered irrelevant many years ago, will suddenly achieve significance when the law later moves in that direction.

With a limit on resources and an opaque selection process, some questions should come to the mind of the conscientious lawyer. How many important precedents slip through the net? How do I know if I have the most relevant authorities to support my argument?

At Justis, we think about this a lot. We are very much of the “no stone unturned” mindset, and that’s why – alongside major and specialist report series – we host an extensive database of court judgments from numerous common law jurisdictions.

We’ve gone to extraordinary lengths to ensure our UK case law collection is the largest available anywhere. We’ve sent teams to courtroom basements across the country to digitise judgments that cannot be found anywhere else. Whether reported or unreported, we endeavour to provide every single case from the superior courts, with coverage dating back further than any other provider. We are proud to say that our database contains more than triple the number of judgments since 1950 than any other.

But providing access to huge amounts of content is one thing – making it accessible is another. It’s simply not feasible to provide busy professionals with mountains of new material and expect them to know where to start.

The era of smart legal tech

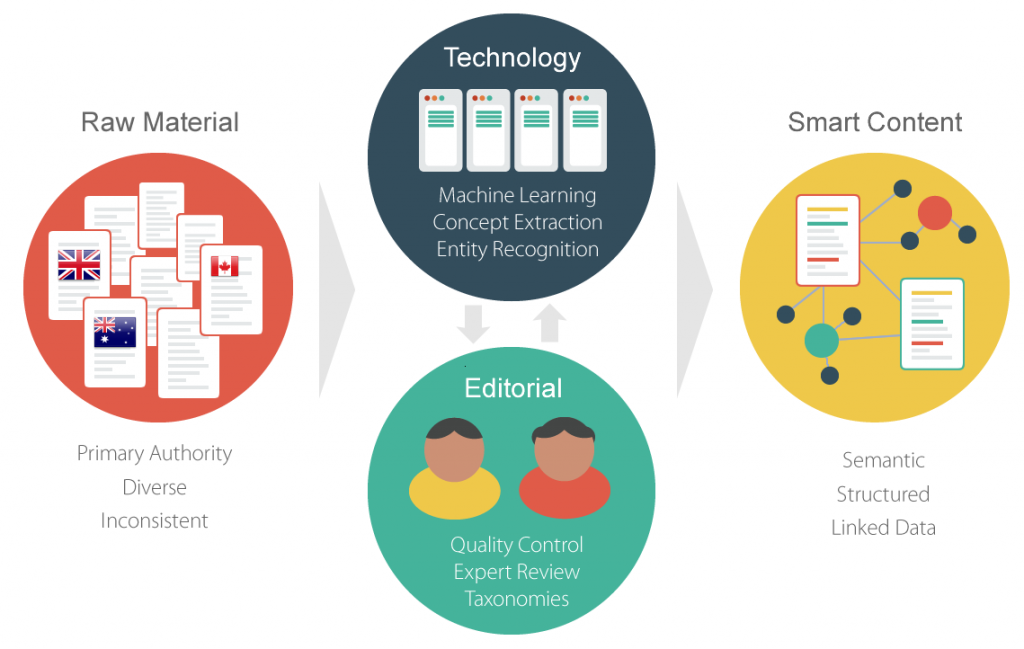

This is where embracing new technological advancements has a fundamental role to play. Beginning with vast amounts of raw, unstructured content, it is now eminently possible to bring order to chaos through well-designed software. Natural language analysis and data-mining can be used to identify and extract legal concepts and arguments. Machine learning algorithms can be used to pinpoint the most important passages in legal texts based on how they have been subsequently cited.

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of this approach (aside from speed, and volume) is consistency – every document in the entire legal corpus can be evaluated in the same way, to the same standard and without bias. For example, all judgments in our database – subsequently reported or otherwise – have been consistently classified against a single, bespoke legal taxonomy. This makes it possible to automatically identify related authorities or supporting arguments – whether they’re lucky enough to have been summarized by a law reporter, or (more frequently) not.

As a matter of principle, every judgment has authority by virtue of its existence, not its reputation or cachet. Intelligent technology allows us to build a more accurate model of the law that acknowledges this. It could be argued these new capabilities don’t simply create an opportunity, but rather an obligation to better understand the law that binds us. With better tools at our disposal, it becomes indefensible to restrict our concerns to an arbitrary subset.

Judgments as authority

For most legal research tasks, court judgments are adequate. However, law reports have a long and rich tradition, and if you find yourself presenting authorities to the higher courts, it is often a requirement that the most authoritative law report be cited.

However, the landscape of legal information delivery is very different now to when the practice of law reporting was conceived.

Law reporting in its modern form began over a century ago, when there was no reliable medium for disseminating the decisions of the courts. This is far from the case today, where most senior court websites regularly publish high-quality, well-formatted judgments. Almost 15 years ago, neutral citations were introduced specifically to facilitate the online publication of judgments by making them easy to identify.

Moving forward, it is likely we will see a less strict insistence on official law reports in court for modern case law, as trustworthy judgments become an equally respected account of the law.

Ireland has been particularly progressive in this area, as judges’ signatures are now added to transcripts so that they can be used in court. In Canada, practice directions requiring presentation of reports have been overturned in a number of provinces. As judiciaries across common law jurisdictions commit to digitisation, this is likely to happen elsewhere.

The “forgotten” 80 per cent

As judgments are rightly recognised as the substantive content of the law, it’s worth remembering that only 20 per cent of cases are reported. Of the 80 per cent of cases which are not, how many are important?

At Justis, we have been able to look at citations across reported and unreported cases. We found that over a two-year period, there were over 300 unreported cases which negatively cited reported cases, meaning the judges in the former questioned the arguments of the latter. Ignoring these leaves a gap in applying the principle of precedent and is a serious risk in litigation.

Moreover, reported cases were not cited as we expected. In our data, for general series (WLR, LR, AELR) we found 23 per cent of reported cases have never been cited and 14 per cent of reported cases cited only once. For specialised series (Family LR, Lloyds LR, Criminal Appeal Reports) 42 per cent of reported cases have never been cited and 16 per cent of reported cases cited only once. This further breaks down the distinction in status of reported and unreported cases, which is entrenched in practice today.

There is no question on the value of law reports – they are indispensable for highlighting key cases and summarising judgments. But we must ensure that practitioners also have meaningful access to unreported judgments, now and in the future.

This is the problem we have sought to address with our new research platform. Justis makes more common law cases than ever before easily accessible. Technology has afforded the opportunity to do this, and this is just the start of finding new ways to navigate complex legal material.

Robin Chesterman is Head of Product at Justis. He studied law at Bristol University before joining Justis as a developer in 2009. His main area of interest is how data science methodologies can be applied to legal content to facilitate better research.

Email RobinChesterman@justis.com. Twitter @RobinChesterman.