With Michael Salter

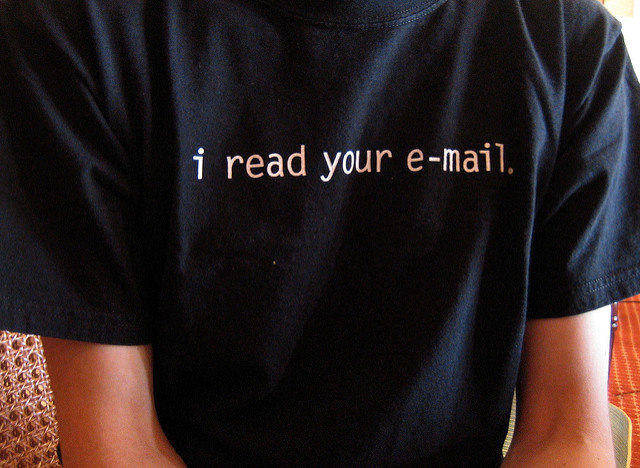

As the line between work and personal life blurs the media has repeatedly made reference to a right to snoop, with headlines such as “Bosses can snoop on workers’ private emails and messages” (The Telegraph), “Britain has a new human right … freedom to spy on employees’ emails” (The Daily Mail) and “Private messages at work can be read by European employers” (BBC News website). These three attention grabbers followed the decision of the ECHR in Bărbulescu v Romania (Application No 61496/08), 12 January 2016. Perhaps predictably, a proper reading of the case reveals that matters are not quite so clear-cut.

Legitimate monitoring at work

Mr Bărbulescu was a sales engineer. He was requested in the course of his employment to create a Yahoo Messenger account, for the specific purpose of communicating with his customers and responding to their enquiries. The employer had a written policy which prevented its computers and other equipment from being used for personal purposes. It transpired that Mr Bărbulescu had indeed used his account for such purposes, which was discovered due to monitoring of the Messenger account by his employer. Prior to presentation by the employer of numerous pages of transcripts of personal messages between Mr Bărbulescu and both his fiancée and his brother, he had denied such personal use. Evidence was also supplied of use of a personal Yahoo Messenger account. Mr Bărbulescu was dismissed for breach of the policy. He challenged the decision.

Mr Bărbulescu failed to obtain a remedy from the domestic courts, which held that the employer was entitled to monitor computers in the workplace as part of its right to check that professional tasks were being completed (in accordance with the relevant Labour Code in force at the time), and that in any event as Mr Bărbulescu had denied personal use, checking was the only way to determine whether his defence was valid.

In his appeal to the ECHR, Mr Bărbulescu relied upon Article 8 of the Convention: the right to respect for private and family life, home and correspondence. Against this argument, Romania contended that there was an inherent illogicality: on the one hand claiming the right to privacy, and on the other denying private use.

The ECHR in reaching its conclusion considered extant case-law relating both to telephone usage in the office and the monitoring of emails (Halford v the United Kingdom (25 June 1997, Reports of Judgments and Decisions 1997‑III; Copland v the United Kingdom (No 62617/00, ECHR 2007‑I). In both cases, the Court had established that, in the absence of a warning as to the prospect of monitoring, there was a legitimate expectation of privacy in respect of telephone and internet communication respectively.

The ECHR however noted that the context of the complaint raised by Mr Bărbulescu was in respect of his dismissal, and thus related to the monitoring of his communications within disciplinary proceedings. It was not the content of the messages, but the fact that they were in breach of the written policy, which led to the dismissal. As such it was for the court to consider, in light of the general prohibition on personal use contained within the policy, whether Mr Bărbulescu retained a reasonable expectation that his communications would not be monitored. The court held that Article 8 was engaged, on the basis that there was a dispute as to whether Mr Bărbulescu had been made specifically aware that his communications could be accessed; that the content was private; and that the personal account had also been accessed.

As a result the court went on to consider whether Romania was in breach of its positive obligation to strike a fair balance between Mr Bărbulescu’s Article 8 rights and the interests of his employer. Mr Bărbulescu had been able to argue his Article 8 points before the domestic courts, which found as a fact that the employer reasonably believed, based on his denial of personal use, that the content of the communications was solely professional. As such the access was legitimate. The access was only to Yahoo Messenger, not other files on the computer, and was thus limited in scope and proportionate. As such, a fair balance was struck, and there was no breach of Article 8.

Even though this was a claim brought against a state for its implementation of the ECHR and the failure of its courts to protect those rights Bărbulescu is an important case, for private employers, but not for the reasons that the media suggest. Rather than being a new snooper’s charter, the ECHR has merely confirmed that a legitimate monitoring policy, applied reasonably and proportionately, is not a breach of Article 8. It was not the content of the messages that led to dismissal, but rather the fact that they were of a personal nature.

Bringing personal communications into the workplace

More recently the Employment Appeal Tribunal in England and Wales determined the matter of Garamukanwa v Solent NHS Trust UKEAT/0245/15/DA, in which it was asked to consider whether Article 8 was engaged when material obtained from Mr Garamukanwa’s smartphone was viewed by the NHS trust. After his relationship with another colleague broke down it was alleged that Mr Garamukanwa commenced a campaign of harassment against the other employee, part of which involved the sending of anonymous emails from various email addresses to various members of the Trust’s management. Although he was arrested by the police, no charges were brought against Mr Garamukanwa. The police did provide the Respondent with a variety of material including photographs from Mr Garamukanwa’s smartphone of the various email addresses from which the anonymous emails were sent. He had no explanation for why he would have these photographs.

In cross-examination and closing submissions before the tribunal, the Claimant advanced an argument, seemingly not put forward at any time beforehand, that the Respondent had breached Article 8. The tribunal concluded that the Claimant had no reasonable expectation of privacy in relation to the emails, and as such Article 8 was not engaged. He appealed the decision to the EAT on the ground, amongst others, that the emails and photographs were entirely private and personal and that whilst the police had power to look at his personal emails and other material, his employers did not.

The EAT found that the protection of Article 8 does in principle extend to private correspondence and communications including, potentially, emails sent at work, where there is a reasonable expectation of privacy. The EAT noted, however, that this expectation was fact-sensitive. In upholding the tribunal and finding that Article 8 was not engaged the EAT noted that the emails had impacted on work-related matters and the employment relationships of the people involved. The emails were sent to the work addresses of the recipients, dealt with work-related matters, employees of the Respondent were affected by the emails and so regardless of the fact that they were personal emails, they were “brought into the workplace” by Mr Garamukanwa.

Conclusion

What both of these cases demonstrate is that emails which clearly relate to personal matters can nevertheless stray into the realm of work and, if so, may lose any protection afforded by Article 8. Thus, the headlines set out at the outset of this article may in fact have some basis in law after all. However, the true message derived from this case law is not a new one. It is simply that employers may uphold their workplace policies preventing personal use and, in investigating a defence of professional use, may check communications so long as a policy is in place, it is highlighted to the employee and warnings are given as to usage.

What these cases indicate, however, is that there is a world of difference between an employer taking shots in the dark and hoping to find incriminating material as opposed to having a legitimate valid reason for the search (as in Bărbulescu). Likewise, when relying on material provided to it by the police in circumstances whereby a harassment campaign has been orchestrated, the right to privacy will not apply. There is a significant difference between being able to check that communications are personal, as opposed to relying upon the content of the same (though even the latter may potentially be proportionate if, for example, the employee is unlawfully sharing business information in a personal capacity). However, “No Human Right to Ignore Employer’s Policy After Lying About Personal Use” would probably sell fewer papers.

Chris Bryden is a barrister at 4 Kings Bench Walk, specialising in civil, employment and family law. Email cxb@4kbw.co.uk. Twitter @BrydenLaw.

Michael Salter is a barrister at Ely Place Chambers, specialising in employment law and costs litigation. Email msalter@elyplace.com. Twitter @Michaelelyplace.

They are joint authors of Social Media in the Workplace (published by Jordans, October 2015, £65).

Image by Paul Downey on Flickr.